2.3 Sulla's Dictatorship

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will understand how Lucius Cornelius Sulla used military force to seize control of Rome, established the precedent for proscriptions and systematic political murder, implemented constitutional reforms as dictator rei publicae constituendae, and why his voluntary abdication failed to restore Republican stability.

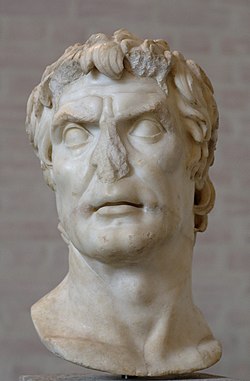

The Patrician Revolutionary

The career of Lucius Cornelius Sulla marked the definitive end of the Roman Republic as a constitutional system. Born into patrician nobility but lacking early wealth or influence, Sulla's rise combined traditional aristocratic values with revolutionary methods that would destroy the very institutions he claimed to defend.

Sulla first gained recognition serving under Marius during the Jugurthine War, where his diplomatic skills secured Jugurtha's capture. This achievement became a source of lasting tension with Marius, as Sulla claimed primary credit for ending the war that had made Marius famous.

During the Social War (91-88 BC), when Rome's Italian allies rebelled to demand citizenship, Sulla distinguished himself as a military commander and built his political profile. His election as consul in 88 BC came with the prestigious Mithridatic command—the expected leadership of Rome's campaign against the eastern king Mithridates VI of Pontus.

However, the radical tribune Publius Sulpicius Rufus proposed transferring this command to Marius, using popular assemblies to override senatorial authority. This humiliation would drive Sulla to take the most fateful decision in Republican history.

Click on any battle to explore the escalating violence that destroyed Republican traditions and established military force as the arbiter of political power.

First March on Rome (88 BC)

Sulla breaks the ultimate taboo

First time a Roman general leads legions against Rome itself

The Unthinkable Becomes Reality

Sulla's march on Rome with six legions shattered the most sacred principle of Republican government—that armies existed to defend the state, not threaten it. His violation of the pomerium (the sacred boundary of Rome) with armed troops was an act of religious sacrilege as well as political revolution.

The march succeeded because resistance collapsed. Most senators fled the city, Marius lacked military forces in Rome, and urban citizens could not oppose disciplined legions. Sulla's propaganda portrayed him as defending legitimate senatorial authority against illegal popular legislation.

Casualties: Minimal military resistance, but enormous constitutional damage

Consequences: Established precedent that military force could override civilian authority; Marius and Sulpicius declared enemies of the state

Marian Counter-Revolution (87 BC)

Violence begets violence

Marius and Cinna seize Rome in Sulla's absence

Terror Comes to Rome

While Sulla campaigned against Mithridates, Marius allied with consul Lucius Cornelius Cinna to retake Rome. Their forces included veteran soldiers, freed slaves, and Italian allies who had supported Sulpicius's citizenship legislation.

The siege of Rome revealed new horrors of civil conflict. Marius's army combined desperation with ruthless determination, and when the city fell, systematic massacres targeted Sulla's supporters and conservative senators.

Marius's brief seventh consulship (86 BC) was marked by proscription lists—the first systematic political murders in Roman history. Though Marius died early in 86 BC, Cinna continued the reign of terror.

Casualties: Hundreds of senators and equestrians executed

Consequences: Established precedent for proscriptions; demonstrated that political defeat meant death

Landing at Brundisium (83 BC)

Sulla returns for revenge

Five veteran legions land in southern Italy

The Avenger Returns

Having concluded peace with Mithridates (though not a complete victory), Sulla returned to Italy with five battle-hardened legions and a burning desire for vengeance. His landing at Brundisium in spring 83 BC marked the beginning of the final phase of civil war.

Sulla's army was smaller than the forces opposing him, but his veterans were disciplined professionals who had campaigned together for years. More importantly, prominent Romans began joining his cause, including the young Pompey who raised three legions in Picenum.

The psychological impact was enormous. Sulla represented legitimacy and order to those exhausted by years of Marian-Cinnan chaos. His promise of constitutional restoration attracted moderates who had initially opposed him.

Forces: 5 legions initially, growing to 23 legions with allied support

Consequences: Triggered mass defections from Marian forces; restored Sullan faction's credibility

Battle of Sacriportus (82 BC)

Marian resistance crumbles

Decisive defeat of consul Marius the Younger

The End of Marian Dreams

At Sacriportus, near Signia, Sulla faced the army of Gaius Marius the Younger (son of the great Marius). The battle demonstrated the superior discipline and experience of Sulla's eastern veterans.

The defeat was catastrophic for the Marian cause. Young Marius fled to Praeneste where he was besieged, and much of his army defected to Sulla. The victory opened the path to Rome and broke Marian morale across Italy.

Sulla's clemency toward defeated enemies in this phase contrasted sharply with his later brutality, suggesting his reign of terror was calculated policy rather than uncontrolled vengeance.

Casualties: Thousands of Marian soldiers killed or captured

Consequences: Collapse of main Marian army; siege of Praeneste begins

Battle of the Colline Gate (82 BC)

The final reckoning

Sulla's ultimate victory outside Rome's walls

Democracy Dies at Rome's Gates

The decisive battle occurred just outside Rome at the Colline Gate, where Sulla faced the last desperate Marian army led by Pontius Telesinus and the Samnites—Rome's ancient Italian enemies who saw this as their final chance to destroy the city.

The battle was ferocious and nearly lost. Sulla's left wing collapsed, and he personally led charges to prevent complete defeat. Only the discipline of his veteran right wing, commanded by Marcus Licinius Crassus, secured victory as darkness fell.

The aftermath was horrific. Sulla ordered the systematic massacre of prisoners, and the sounds of mass execution in the nearby Villa Publica were audible to senators meeting in the Temple of Bellona. When senators asked about the noise, Sulla replied: "Pay no attention—it's just some criminals being punished."

Casualties: 50,000+ killed in battle and subsequent massacres

Consequences: End of organised resistance; beginning of Sulla's reign of terror

Sulla's proscriptions were the first systematic political purges in Roman history. Click on names below to discover the fates of those condemned to death without trial.

PROSCRIPTI - ENEMIES OF THE PEOPLE

"These men are condemned. Any citizen may kill them for reward. Their property is forfeit to the state."

Crime: Leading Samnite forces against Rome at Colline Gate

Fate: Killed in battle, head displayed in Forum as warning to other Italian rebels

Significance: Represented last hope of non-Roman Italy to destroy Rome; his death ended centuries of Italian resistance

Crime: Continuing resistance to Sulla in Spain

Fate: Escaped to Spain, established independent state, assassinated by his own lieutenant in 72 BC

Significance: Proved that talented generals could create rival Roman states in the provinces

Crime: Kinship with Marius and popular economic policies

Fate: Tortured and mutilated by Catilina at the tomb of Lutatius Catulus, whom Marius had killed

Significance: Demonstrated that even family connections to enemies meant death; showed ritualistic nature of revenge

Crime: Supporting Marian cause and opposing Sulla's return

Fate: Murdered while clinging to altar of Vesta—violation of sacred asylum

Significance: Showed that not even Rome's highest religious office provided protection; desecration of sacred law

Crime: Association with Marian faction through family connections

Fate: Executed, leaving young Julius Caesar vulnerable as a marked man

Significance: Nearly included Julius Caesar himself on proscription lists; showed how civil war could destroy entire family lines

Crime: Leading Marian resistance as consul and general

Fate: Fled to Africa, captured and executed by Pompey on Sulla's orders

Significance: Showed that exile provided no safety; Pompey's ruthless efficiency earned him the nickname "teenage butcher"

Crime: Possessing valuable estates coveted by Sulla's supporters

Fate: Murdered for his property; estates sold at fraction of value to reward loyalty

Significance: Proved that wealth alone could be a death sentence; proscriptions became method of economic redistribution

Total Estimated Deaths: 2,000+ Senators and Equestrians

Plus thousands of other citizens, slaves, and supporters

Click on each category to explore how Sulla's reforms attempted to prevent future Mariuses—while creating the conditions for future Caesars.

Revolutionary Constitutional Changes

Click on any reform above to explore how Sulla's reforms attempted to prevent future Mariuses—while creating the conditions for future Caesars.

Sulla's reforms attempted to prevent future Mariuses whilst inadvertently creating the conditions for future Caesars.

Creating a Sullan Senate

Sulla expanded the Senate from approximately 300 to 600 members, primarily through appointing his own supporters and loyalists. This diluted traditional senatorial families whilst ensuring his faction dominated the expanded body.

Judicial Reforms: Returned jury service in the courts (quaestiones) exclusively to senators, reversing Gracchan legislation that had given equestrians judicial power. This restored senatorial control over prosecution of provincial governors and other major crimes.

Provincial Commands: Required praetors and consuls to remain in Rome during their year of office, taking provincial commands only afterward as promagistrates. This separated civil and military authority.

Long-term Impact: Created a more compliant Senate in the short term, but the expansion with political appointees actually weakened traditional senatorial authority and prestige.

Destroying Popular Power

Sulla systematically dismantled tribunician authority, the office that had launched the careers of the Gracchi, Saturninus, and Sulpicius. His restrictions were designed to make the tribunate powerless and unattractive.

Legislative Ban: Tribunes were prohibited from proposing legislation to the popular assemblies, eliminating their ability to bypass senatorial opposition through direct appeals to the people.

Career Dead-end: Tribunes were barred from seeking higher magistracies, making the office a terminal position that ambitious politicians would avoid.

Veto Limitations: Though tribunes retained their traditional veto power, the legislative ban made this largely irrelevant since they couldn't propose alternative measures.

Long-term Failure: These restrictions were gradually reversed. Pompey and Crassus restored tribunician power in 70 BC, and later popularis politicians like Caesar used the tribunate more effectively than ever.

Bureaucratic Control

Sulla formalised the cursus honorum (course of offices) with strict regulations designed to prevent rapid political advancement and ensure experienced leadership.

Age Requirements: Set minimum ages for each office—30 for quaestor, 39 for praetor, 42 for consul—preventing young firebrands from gaining power too quickly.

Mandatory Intervals: Required two-year gaps between holding consecutive magistracies, slowing political careers and giving the Senate more time to assess candidates.

Office Sequence: Mandated that candidates hold quaestorship before praetorship, and praetorship before consulship, creating a predictable career ladder.

Numbers Increase: Raised annual magistrates from 8 to 20 praetors and maintained 2 consuls, providing more administrative positions for the expanded Senate.

Unintended Consequences: Created more competition for the consulship, the only office that mattered for true distinction, intensifying rather than reducing political rivalry.

Closing the Stable After the Horses Bolted

Having used military force to seize power, Sulla attempted to prevent future generals from following his example—an effort doomed by its own contradictions.

Provincial Boundaries: Strictly defined provincial commands and prohibited governors from leading armies outside their assigned territories without Senate permission.

Treason Laws: Expanded definitions of treason (maiestas) to include actions that diminished state authority, theoretically making it illegal to march on Rome.

Command Restrictions: Limited the duration of provincial commands and required Senate approval for extensions, preventing generals from building long-term client relationships with troops.

Fundamental Flaw: Sulla's reforms could not address the root problem—professional armies loyal to their commanders rather than the state. The very system Marius had created made these restrictions unenforceable.

Future Violations: Pompey, Caesar, and others would repeatedly violate these restrictions, proving that constitutional law cannot constrain those who control military force.

Sulla transformed the ancient office of dictator from emergency leadership into unlimited personal power.

Traditional Dictator

- Appointed for 6-month maximum

- Specific military emergency

- Limited to assigned task

- Appointed by consul with Senate approval

- Resigned when task completed

- Subject to later accountability

Last used: 202 BC (Hannibalic War)

Sulla's Dictatorship

- No time limit specified

- Constitutional reform mandate

- Unlimited power scope

- Self-appointed through military force

- Voluntarily abdicated (unprecedented)

- Immunity from prosecution

Duration: 82-79 BC (3+ years)

The Revolutionary Precedent

Sulla's dictatorship established that supreme power could be seized through military force and used for unlimited political transformation. His voluntary resignation paradoxically made the precedent more dangerous—it suggested that dictatorial power could be temporary and legitimate, encouraging future ambitious generals to follow his example.

Modern historians debate whether Sulla should be understood as a conservative restorer of Republican traditions or a revolutionary destroyer of constitutional government. His own propaganda emphasised restoration, but his methods were unprecedented and destructive.

Conservative Interpretation: Sulla genuinely sought to restore traditional senatorial government and prevent future popularis revolutions. His reforms strengthened aristocratic institutions and his voluntary abdication proved his republican intentions.

Revolutionary Interpretation: Sulla's methods—military seizure of power, systematic proscriptions, unlimited dictatorship—destroyed the Republican system he claimed to defend. His reforms failed because they addressed symptoms rather than causes.

The Tragic Hero View: Sulla understood that the Republic was dying but believed authoritarian methods could revive it. His tragedy was using the disease to cure itself—employing illegal means to restore legal government.

The most compelling interpretation sees Sulla as transitional—neither purely conservative nor revolutionary, but a figure caught between the old Republican world and the new imperial reality that his own actions helped create.

Sulla's career provided a template for future Roman strongmen, demonstrating both the possibilities and limitations of using military force for political transformation. His precedents would be studied and adapted by Pompey, Caesar, and Augustus.

Military Supremacy

Proved that disciplined armies could overcome constitutional opposition and popular resistance. Future generals learned that military victory translated into political authority.

Systematic Terror

Established proscriptions as an effective method for eliminating political opposition and redistributing wealth to supporters. The precedent made future civil wars more brutal.

Constitutional Manipulation

Showed how ancient offices could be transformed for unprecedented purposes. Later strongmen would similarly manipulate Republican institutions to legitimise autocratic power.

The Abdication Model

His voluntary retirement suggested that temporary dictatorship could be legitimate and limited, making the precedent more attractive to future ambitious politicians.

Ultimately, Sulla's reforms failed because they could not resolve the fundamental contradiction he had created: professional armies loyal to generals rather than the state made constitutional government impossible, yet his solutions required constitutional means to implement. He had broken the machine he was trying to repair.

Critical Analysis Question

Did Sulla's voluntary abdication prove his republican sincerity, or did it simply make his precedent more dangerous for future strongmen?

Consider: the effectiveness of his constitutional reforms, the precedent set by his methods, the reaction of contemporaries, and the careers of Pompey and Caesar who followed his example.