2.2 Marius and Military Reform

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will understand how Gaius Marius transformed Roman military recruitment and created client armies loyal to commanders rather than the state, how his career established precedents for exceptional commands, and why his rivalry with Sulla marked the beginning of civil war.

The Novus Homo from Arpinum

The rise of Gaius Marius marks one of the most significant turning points in the transformation of the Roman Republic. Born in Arpinum in 157 BC, Marius came from an equestrian background but lacked senatorial connections. He represented everything the traditional elite despised—a novus homo (new man) who defied social expectations and rose through merit rather than noble birth.

Marius presented himself as an outsider—honest, hardworking, and immune to the corruption of the nobiles. His early political and military career benefited from patronage under Scipio Aemilianus, gaining valuable experience during the Numantine War.

His defining moment came with the war in Numidia against King Jugurtha, a conflict that had dragged on due to bribery and senatorial incompetence. Promising to end the war swiftly, Marius was elected consul in 107 BC, backed by popular support rather than aristocratic connections—a direct challenge to the traditional workings of Republican politics.

Revolutionary Military Changes

Click on any reform above to explore how Marius transformed the Roman army. These changes solved immediate military problems but created long-term political crises that would ultimately destroy the Republic.

Marius didn't just reform the army—he revolutionised the relationship between soldiers, generals, and the state.

The End of the Citizen-Militia

Traditional Roman armies were composed of assidui—landowning citizens who could afford their own equipment. This system worked well for local wars but created severe manpower shortages during prolonged overseas campaigns.

Marius abolished property qualifications entirely, allowing the capite censi (landless poor) to enlist for the first time. These men, previously excluded from military service, eagerly joined for regular pay and the promise of land grants upon retirement.

The change was immediately practical—Rome could now field much larger armies from the growing urban population. Men who had lost their farms to debt or warfare could rebuild their lives through military service.

However, this created a fundamental shift in loyalty. Citizen-soldiers had fought to protect their own property and communities. Professional soldiers fought for pay and rewards that only their generals could provide.

Uniform Equipment and Training

Before Marius, soldiers provided their own equipment, leading to inconsistent quality and capabilities. Wealthy soldiers had better armour and weapons, whilst poor citizens made do with basic gear.

Marius standardised equipment across the legions, with the state providing uniform weapons, armour, and training. Every soldier received the same gladius, scutum, and pilum.

He also introduced rigorous, systematic training programmes that transformed farmers and labourers into professional soldiers. Veterans became trainers for new recruits, creating institutional knowledge that persisted across campaigns.

The famous Marian mule reform required soldiers to carry their own equipment on marches, increasing army mobility and reducing dependence on supply trains.

These changes created more effective, disciplined armies that could sustain longer campaigns and adapt to different enemies across the Mediterranean world.

From Seasonal Service to Career Soldiers

Traditional Roman service was seasonal—farmers served during campaign season then returned to their land. Marius created the first truly professional Roman army with soldiers serving for decades rather than years.

Professional soldiers developed skills and experience impossible under the old system. They learned engineering, siege warfare, logistics, and tactics that made Roman armies increasingly formidable.

Long service also created strong bonds between soldiers and their commanders. Officers who led men through multiple campaigns earned intense personal loyalty that transcended institutional allegiance.

The army became a career path for ambitious men from humble backgrounds, offering social mobility previously available only through politics or trade.

However, professional soldiers had no civilian lives to return to between campaigns. They depended entirely on their generals for pay, promotion, and eventually retirement provision.

Land Grants and Veteran Settlement

Since professional soldiers served for 16-20 years, they needed provision for retirement. Marius promised land grants to veterans, creating colonies throughout the Roman world.

These settlements served multiple purposes: they provided for veteran welfare, spread Roman culture to frontier regions, and created strategic reserves of experienced soldiers.

However, land grants required Senate approval and funding, which conservative senators often refused. This forced generals to seek alternative sources—conquered territory, confiscated estates, or political alliances.

Veterans became a powerful political constituency, supporting politicians who promised them land and opposing those who threatened their settlements.

The promise of land also attracted recruits who saw military service as their only path to property ownership and social advancement.

When the Senate refused veteran rewards, generals had strong incentives to use military force against the state itself—as Marius, Sulla, Pompey, and Caesar would all eventually do.

The Price of Military Efficiency

Marius's reforms created the most effective military machine in the ancient world, but at enormous political cost. Soldiers now served generals rather than the state, fundamentally altering the balance of Republican power.

Generals who could promise land, booty, and advancement commanded intense personal loyalty. Veterans would follow successful commanders anywhere—including against Rome itself.

The client army system gave ambitious politicians military power independent of traditional institutions. The Senate could no longer control generals who commanded devoted professional forces.

Every subsequent crisis—Sulla's march on Rome, Pompey's eastern commands, Caesar's Gallic Wars—stemmed from generals using Marian-style armies for political purposes.

The reforms also created a cycle of violence. Veterans needed land, which required conquest or confiscation, which created new enemies and necessitated larger armies, which needed more land for their veterans.

Marius solved Rome's immediate military problems but created the conditions for civil war and eventual autocracy.

Between 104 and 100 BC, Marius faced the greatest external threat Rome had seen since Hannibal. His unprecedented five consecutive consulships saved the Republic but shattered constitutional norms.

Constitutional Crisis and Military Triumph

Click on any event above to explore how the Cimbric crisis transformed Marius from a controversial reformer into Rome's greatest military hero—whilst simultaneously undermining Republican institutions.

The threat was real, but the constitutional cost was enormous.

The Northern Threat Materialises

From 113 BC onwards, migrating Germanic and Celtic tribes began devastating Roman territories in Gaul and threatening Italy itself. The Cimbri and Teutones had already defeated several Roman armies, exposing the weaknesses of traditional recruitment.

These weren't typical barbarian raids but massive population movements—entire tribes with families, livestock, and possessions seeking new lands. Their sheer numbers overwhelmed conventional Roman tactics.

Traditional Roman armies, composed of seasonal citizen-soldiers, proved inadequate against an enemy that could fight year-round and had nothing to lose.

The defeats revealed that Rome's military system, designed for Italian warfare, was poorly suited to defending vast frontiers against determined migrating peoples.

Senatorial generals, appointed through political connections rather than military competence, repeatedly failed against enemies who had spent years perfecting their war-making skills.

The Arausio Catastrophe (105 BC)

At Arausio (modern Orange), two Roman armies under Gnaeus Mallius Maximus and Quintus Servilius Caepio suffered Rome's worst defeat since Cannae. Approximately 80,000 Romans and allies were killed.

The disaster stemmed from aristocratic rivalry—Caepio refused to cooperate with Mallius because of class prejudice, allowing the barbarians to defeat divided Roman forces separately.

The scale of losses was staggering. Entire legions were annihilated, leaving northern Italy virtually defenceless. Panic gripped Rome as barbarian victory seemed to open the path to the city itself.

The defeat discredited traditional military leadership and demonstrated that aristocratic birth was no guarantee of military competence.

Popular opinion turned decisively against the nobiles who had led these disasters, creating demand for proven military talent regardless of social origin.

Emergency Election in Absentia (104 BC)

Facing potential annihilation, Rome took the unprecedented step of electing Marius consul whilst he was still completing his campaign against Jugurtha in Africa. This violated the principle that candidates must be present in Rome for elections.

The emergency election demonstrated how crisis could override constitutional norms. Popular fear of the barbarians was so intense that traditional procedures seemed irrelevant.

Marius was granted extraordinary authority to recruit and train new armies using his reformed system. The traditional property qualifications were formally abandoned as Rome mobilised every available man.

This marked the beginning of his five consecutive consulships (104-100 BC), shattering the Republican principle of annual magistrates and shared power.

The precedent established that exceptional circumstances could justify exceptional commands—a principle later exploited by Pompey, Caesar, and other ambitious generals.

Victory at Aquae Sextiae (102 BC)

Marius first confronted the Teutones at Aquae Sextiae (modern Aix-en-Provence). His reformed legions, professional and disciplined, proved devastatingly effective against barbarian mass attacks.

The battle demonstrated the superiority of professional soldiers over both citizen-militia and barbarian warriors. Marius's men maintained formation under pressure and executed complex tactical manoeuvres that would have been impossible for traditional forces.

Reportedly, 100,000 Teutones were killed and 90,000 captured, with their king Teutobod taken prisoner. The victory was so complete that the Teutones effectively ceased to exist as a tribal entity.

Marius distributed booty generously among his soldiers, strengthening their personal loyalty and demonstrating the rewards of following a successful general.

The victory validated both Marius's military reforms and his personal command, making him indispensable for the continuing barbarian threat.

The Final Victory at Vercellae (101 BC)

The Cimbri had meanwhile invaded northern Italy, but Marius, joined by his colleague Quintus Lutatius Catulus, met them at Vercellae in the Po valley.

The combined Roman armies utterly destroyed the Cimbri. According to sources, 140,000 barbarians were killed and 60,000 captured, including women and children who had accompanied the migration.

The battle showcased Roman tactical superiority and Marius's ability to coordinate multiple armies. Professional soldiers proved they could execute sophisticated battle plans that defeated even numerically superior enemies.

Marius cleverly shared credit with Catulus, maintaining the fiction of collegiate command whilst ensuring his political position remained secure.

The victory ended the Cimbric threat permanently and secured Rome's northern frontiers for generations. Italy was safe, and Marius was the undisputed architect of salvation.

"Third Founder of Rome" (100 BC)

Marius returned to Rome as the greatest military hero since Scipio Africanus. Popular acclaim hailed him as the "third founder of Rome," after Romulus and Camillus.

His five consecutive consulships had saved the Republic, but they also established dangerous precedents. Annual magistrates and term limits—fundamental Republican principles—had been abandoned when crisis demanded exceptional leadership.

Marius's success demonstrated that military competence could override traditional qualifications for high office. Birth, connections, and rhetorical skill mattered less than proven ability to win battles.

However, his extended command had created the first truly personal army in Roman history. Veterans loyal to Marius personally now expected rewards that only he could provide.

The constitutional crisis was postponed, not resolved. Marius had saved Rome from barbarians, but his methods had weakened the very institutions he sought to protect.

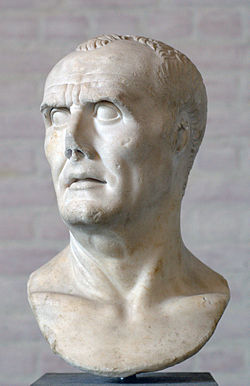

Gaius Marius

The Popularis General

• Novus homo from Arpinum

• Seven-time consul

• Victor over Jugurtha and the Cimbri

• Creator of professional armies

• Supported by urban masses and veterans

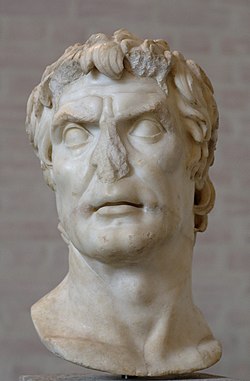

Lucius Cornelius Sulla

The Optimate Champion

• Patrician aristocrat

• Brilliant military tactician

• Defender of senatorial privilege

• First to march on Rome

• Backed by conservative elite

From Partnership to Civil War

The rivalry between Marius and Sulla began as professional competition but escalated into the first Roman civil war, establishing precedents that would destroy the Republic.

The Path to Civil War

Click on any stage above to explore how the relationship between Marius and Sulla evolved from partnership to deadly rivalry, establishing the pattern of personal conflicts that would ultimately destroy the Republic.

This was the first time Roman armies had been used against the Roman state itself.

Early Partnership: Master and Student (107-104 BC)

The relationship between Marius and Sulla began as a traditional mentor-protégé dynamic during the Jugurthine War. Sulla served as Marius's quaestor in 107 BC, learning military command whilst supporting his superior's campaigns against King Jugurtha.

Sulla demonstrated exceptional diplomatic and military skills during this period. His most notable achievement was negotiating Jugurtha's surrender through diplomatic contacts with the Mauretanian king Bocchus, who betrayed his son-in-law to Roman custody.

However, even during this partnership, tensions emerged over credit for the war's successful conclusion. Sulla commissioned a signet ring depicting himself receiving Jugurtha's surrender from Bocchus, subtly claiming primary responsibility for the victory that had made Marius famous.

The partnership worked because both men benefited: Marius gained a capable subordinate who could handle delicate negotiations, whilst Sulla learned command skills and built his reputation under Rome's most successful general.

This period established the pattern of their relationship—Sulla's aristocratic connections and diplomatic finesse complementing Marius's military reforms and popular appeal, but with underlying competition for recognition and glory.

Growing Rivalry: Competition for Glory (104-91 BC)

As both men advanced their careers, professional cooperation gave way to personal rivalry. Sulla's aristocratic background and growing military reputation made him less willing to serve in subordinate roles, whilst Marius's consecutive consulships during the Cimbric Wars established him as Rome's premier general.

During the Cimbric campaigns, Sulla served under various commands but increasingly sought independent opportunities to demonstrate his own tactical brilliance. His service with Catulus at Vercellae allowed him to share credit for the victory whilst maintaining distance from Marius's direct authority.

The fundamental conflict emerged from their different political philosophies and social positions. Marius represented popularis politics—appealing to masses and veterans whilst challenging traditional elite privilege. Sulla embodied optimate values—defending senatorial authority and aristocratic prerogatives against popular movements.

Their rivalry intensified during the 90s BC as both sought prestigious commands in new wars. Sulla's election to the praetorship in 93 BC and successful campaigns in Asia demonstrated that he no longer needed Marius's patronage to advance his career.

Personal animosity was compounded by factional politics. Marius's alliance with popularis politicians like Saturninus alienated conservative senators, whilst Sulla's optimate connections made him their natural champion against Marian influence.

By 91 BC, both men commanded independent power bases—Marius through veteran loyalty and popular support, Sulla through aristocratic networks and proven military competence. The stage was set for direct confrontation.

The Mithridatic Command Crisis (88 BC)

The immediate crisis that sparked civil war arose from competition for the lucrative command against King Mithridates VI of Pontus, who had massacred thousands of Romans in Asia and invaded Roman territories. This promised to be the most prestigious and profitable military assignment in a generation.

Sulla, as consul in 88 BC, received the Mithridatic command through normal constitutional processes. The Senate, dominated by optimates, naturally favoured their aristocratic champion over the popularis Marius, who was now 69 years old and seemed past his military prime.

However, Marius was unwilling to retire quietly. He allied with the radical tribune Publius Sulpicius Rufus, who proposed legislation transferring the eastern command from Sulla to Marius. This violated constitutional precedent but had popular support from Marius's veterans and urban masses.

Sulpicius's proposal also included controversial measures to enfranchise Italian allies and recall political exiles, creating a comprehensive popularis programme that threatened optimate interests. When the Senate declared a public holiday to prevent voting, Sulpicius's supporters used violence to force the measure through.

The transfer of commands by popular legislation rather than senatorial assignment represented a constitutional revolution. It established the precedent that assemblies could override traditional senatorial prerogatives in military appointments, fundamentally altering the balance of Republican power.

Faced with the loss of his command and the humiliation of being superseded by his former commander, Sulla made the unprecedented decision to march on Rome with his legions—crossing the Rubicon of Republican politics fifty years before Caesar's more famous transgression.

The Unthinkable: Roman Legions Against Rome (88 BC)

Sulla's march on Rome with six legions shattered the most fundamental taboo of Republican politics—the principle that Roman armies existed to protect the state, not to threaten it. His soldiers, recruited through Marius's reforms and loyal to their commander, followed him despite the constitutional crisis.

The march revealed how Marius's military reforms had created new dangers. Professional soldiers, dependent on their generals for rewards and advancement, would follow successful commanders even against Rome itself. The client-army system made civil war not just possible but inevitable.

Sulla's justification was constitutional—he claimed to be defending legitimate senatorial authority against illegal popular legislation and tribunician violence. His propaganda portrayed Marius and Sulpicius as revolutionaries destroying traditional Republican government through mob rule and intimidation.

The march succeeded because resistance collapsed. Most senators had fled the city, Marius lacked military forces in Rome, and the urban population could not oppose disciplined legions. Sulla occupied the capital and immediately reversed Sulpicius's legislation whilst declaring his enemies public enemies.

Marius and Sulpicius were forced to flee into exile, with Sulpicius killed during his escape. Sulla restored the constitutional order but at enormous cost—he had demonstrated that military force could override civilian authority and established precedents that would be repeatedly exploited by future generals.

However, Sulla's position remained precarious. He controlled Rome but needed to depart for the Mithridatic campaign, leaving his enemies free to return and reverse his measures. The crisis was postponed, not resolved.

Marius's Revenge: The Terror of 87-86 BC

As soon as Sulla departed for the east, Marius began plotting his return. Allied with the consul Lucius Cornelius Cinna, who had promised to restore him from exile, Marius recruited forces from his veterans and Italian allies who had supported Sulpicius's citizenship legislation.

Marius's return in 87 BC triggered the first extended period of civil warfare in Roman history. His forces, combining veteran loyalty with desperation born of proscription, fought with savage intensity against Sulla's supporters who had remained in Rome.

The siege of Rome revealed new horrors of internal conflict. Marius's army included slaves promised freedom and foreigners seeking Roman citizenship, creating a coalition that terrified traditional Romans. When the city fell, systematic massacres targeted Sulla's supporters and conservative senators.

Marius's seventh consulship in 86 BC was brief but traumatic for the Roman elite. His reign of terror eliminated many of Sulla's key allies through proscription lists—systematic executions of political enemies whose property was confiscated for the state and loyal followers.

The violence established precedents that would characterise all subsequent civil wars. Political opponents were not merely defeated but eliminated, their families threatened, and their property redistributed. Compromise became impossible when defeat meant death.

Marius died in January 86 BC, just days into his seventh consulship, but his legacy of violence continued under Cinna's dominance. Rome remained under popularis control until Sulla's eventual return from the east, but the Republic's constitutional traditions had been irreparably damaged.

The Marian terror demonstrated that the new military system made traditional Republican competition impossible. When armies served generals rather than the state, political rivalry inevitably became military conflict, and military conflict necessarily involved the destruction of opponents.

In 100 BC, Marius allied with the radical tribune Lucius Appuleius Saturninus, who pushed for legislation to grant land to Marius's veterans. This alliance revealed the impossible position Marius occupied between popular expectations and elite opposition.

When Saturninus's supporters murdered a political rival during election violence, the Senate passed the senatus consultum ultimum, authorising Marius to restore order. Caught between his popularis ally and constitutional duty, Marius chose the latter.

Marius suppressed Saturninus's uprising, but his image was permanently tarnished. Populares could no longer trust his loyalty, whilst optimates never forgot his earlier reforms and alliances. He appeared as a man without a faction—too radical for conservatives, too moderate for revolutionaries.

The affair demonstrated the impossible contradictions of Late Republican politics. Military success required popular support, but popular support threatened elite interests. Marius's attempt to bridge this divide satisfied no one and prefigured the civil wars to come.

Historians continue to debate whether Marius should be seen as a saviour of the Republic or a destroyer of its values. His reforms were militarily necessary—Rome needed larger, more professional armies—but the political price was enormous.

Military Innovation

Created the most effective military force in the ancient world, enabling Roman expansion and frontier defence that would have been impossible under the old system.

Client Armies

Professional soldiers loyal to commanders rather than the state gave ambitious generals independent power bases that could challenge traditional institutions.

Constitutional Precedents

Multiple consulships and emergency commands established that exceptional circumstances could override fundamental Republican principles of shared power and term limits.

Social Mobility

Military service offered unprecedented opportunities for advancement, but also created expectations for rewards that the state struggled to fulfil.

Ultimately, Marius should be understood as a transitional figure. He did not destroy the Republic, but he fatally weakened the institutions that had preserved it for centuries. His career stands as a warning of how even necessary reforms can have devastating unintended consequences when constitutional safeguards are eroded.

Critical Analysis Question

Were Marius's military reforms an inevitable response to changing circumstances, or did they create more problems than they solved?

Consider: the military challenges Rome faced, alternative approaches to recruitment and organisation, the political consequences of professional armies, and whether the Republic could have survived without these changes.