1.5 Political Factions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will understand the key political factions of the Late Republic, how politicians used factional labels for advantage, and why modern historians question whether these groups were genuine ideological movements or convenient rhetorical tools.

Unlike modern political systems with formal parties, the Roman Republic was structured around informal factions: loose groupings of individuals who shared similar aims, outlooks, or mutual advantage. The key divisions of the Late Republic are often described using three labels—optimates, populares, and boni—though these terms can be misleading if treated as rigid or unified parties.

Understanding these factions is essential for grasping Late Republican politics, but we must remember that politicians often switched between them when convenient. The same man might be called an optimate by supporters and a dangerous radical by enemies, showing how factional labels were as much about rhetoric as reality.

Late Republican politics was dominated by competing factions that claimed to represent different values and constituencies. Explore each faction to understand their beliefs, methods, and key figures—but remember that these labels were often more rhetorical tools than ideological programmes.

Political Labels and Reality

Click on any faction above to explore its characteristics, methods, and key figures. These labels provided a vocabulary for Republican politics, but politicians often moved between them as circumstances changed.

Key insight: Modern historians increasingly question whether these were genuine ideological movements or simply convenient labels used to justify actions and attack enemies. The same policies might be called "traditional" or "revolutionary" depending on who was describing them.

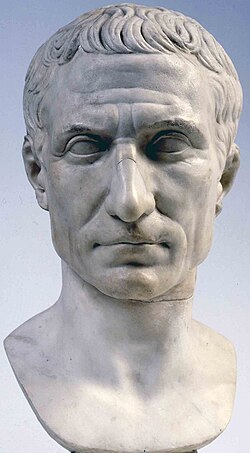

Optimates: The Self-Proclaimed "Best Men"

The optimates (meaning "the best men") were the self-proclaimed defenders of traditional Republican values. They aimed to protect the authority of the Senate, uphold the mos maiorum (customs of the ancestors), and resist threats to the existing order.

Key beliefs and strategies:

- Use of the Senate and traditional magistracies to exercise control

- Resistance to reform movements, especially land redistribution

- Preference for gradualism and legal procedure over revolutionary change

- Opposition to popular assemblies bypassing senatorial authority

- Defence of property rights and existing social hierarchies

Methods: Optimates preferred to work through established institutions—the Senate, consuls, and traditional magistrates. They used legal procedures, senatus consulta, and constitutional precedent to block reforms they saw as dangerous.

Social base: Primarily drawn from established senatorial families, wealthy landowners, and those who benefited from the existing system. They claimed to represent Roman tradition against demagogic innovation.

Famous optimates: Cato the Younger was unflinching in his defence of tradition and moral purity. Cicero (at times) promoted concordia ordinum but opposed demagogues like Clodius. Bibulus attempted to block Caesar's legislation as consul.

Contradictions: Despite claiming to defend the Republic, optimates sometimes supported extraordinary commands and even dictatorships when it served their interests. Sulla's dictatorship was backed by many optimates who benefited from his proscriptions and constitutional changes.

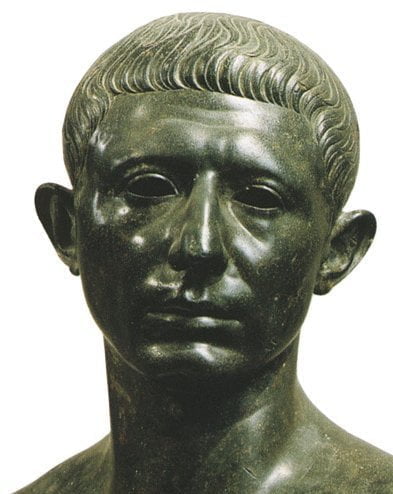

Populares: Bypassing the Senate

The populares ("men of the people") used the popular assemblies and tribunes of the plebs to bypass senatorial opposition and appeal directly to the Roman people (populus Romanus). Their policies often focused on land redistribution, grain supply, citizenship rights, and military rewards.

Tactics and outlook:

- Appeal to the urban poor and Italian allies seeking citizenship

- Use of laws and plebiscites pushed through the Tribal Assembly

- Rhetoric of libertas, justice, and reform against senatorial privilege

- Public works and entertainment to gain popular support

- Military settlements and veteran colonies for land distribution

- Alliance with tribunes of the plebs for legislative power

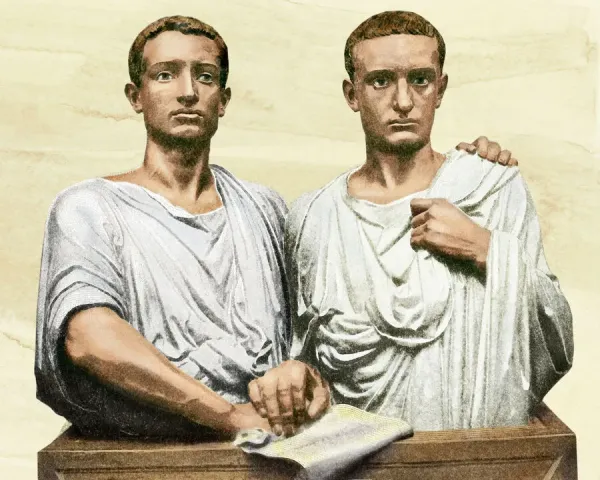

Key populares: Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus were pioneering land reformers who challenged senatorial privilege and paid with their lives. Julius Caesar used popular support and public generosity to gain power, combining popularis rhetoric with personal ambition. Clodius Pulcher was a tribune who used populism and violence to dominate politics.

Important caution: "Popularis" does not mean left-wing or democratic in a modern sense. Populares could be wealthy aristocrats manipulating the crowd for personal advancement. Caesar was one of Rome's richest men, yet used popularis methods to achieve unprecedented power.

Popular policies: Land redistribution for veterans and poor citizens, subsidised grain distributions (annona), public works providing employment, extension of citizenship to Italian allies, and debt relief measures.

Opposition tactics: Optimates accused populares of being demagogues who corrupted the people with bribes and false promises. They claimed popularis policies would bankrupt the state and destroy traditional Roman values.

Boni: The Moral High Ground

The boni ("the good men") were a conservative label for those senators regarded as morally upright and politically reliable. The term often overlapped with the optimates, though it implied personal character as well as political alignment.

Characteristics:

- Emphasis on personal virtue and moral integrity

- Opposition to corruption, bribery, and political violence

- Support for traditional Roman values and customs

- Resistance to revolutionary change and radical reform

- Preference for consensus and constitutional procedure

Cicero's vision: Promoted by Cicero to refer to men of virtus, auctoritas, and fides. He envisioned the boni as a moral coalition transcending class divisions—senators and equites united by shared values rather than economic interests.

Rhetorical function: The term was used rhetorically to exclude political opponents as dangerous or corrupt. By definition, anyone opposing the boni was among the "bad men" (mali) who threatened the Republic's moral foundations.

Key figures: Cicero saw himself as the leading bonus, defending the Republic through oratory and moral authority. Cato the Younger embodied the boni ideal through his inflexible virtue and resistance to corruption.

Practical limitations: The boni ideal was often more rhetorical than real. Many "good men" engaged in the same corrupt practices they condemned in others. The moral high ground was frequently claimed by politicians whose actions contradicted their principles.

Historical irony: The boni failed to prevent the Republic's collapse despite their claims to moral superiority. Their inflexibility and inability to compromise may have contributed to the political breakdown they sought to prevent.

Historian Mary Beard in SPQR (2015) argues that Roman political labels like "popularis" and "optimate" functioned primarily as weapons of political discourse rather than meaningful ideological categories.

Beard's key argument: These terms were "political insults and rallying cries" designed to discredit opponents and justify actions. Calling someone a "demagogue" or "enemy of the people" was more important than actual policy differences.

Evidence that supports Beard's view:

- Cicero's rhetoric: He called the same policies "traditional" when he supported them and "revolutionary" when opponents proposed them

- Caesar's flexibility: Used popularis methods while accumulating unprecedented personal power

- Pompey's changes: Moved from popularis to optimate based on convenience, not conviction

- Contemporary confusion: Ancient sources often disagree about which faction politicians belonged to

Evidence that challenges Beard's view:

- Policy consistency: Populares consistently supported land redistribution, grain subsidies, and citizenship extension

- Cato's principles: Some politicians like Cato never changed their factional alignment despite personal cost

- Social bases: Different factions appealed to different constituencies (urban poor vs. landed elite)

- Gracchi legacy: The popularis "tradition" inspired later politicians like Saturninus and Sulpicius

Critical thinking question: Does the evidence from Late Republican politics support Beard's view that factional labels were primarily rhetorical weapons, or do you think there were genuine ideological differences between optimates and populares? Consider both the consistency of policies and the flexibility of politicians in your answer.

Modern relevance: Beard's analysis helps us understand how political language works in any system—labels can be used to attack opponents even when the underlying policies are similar. This insight applies to both ancient Rome and contemporary politics.

The conflicts between factions—or between individuals who used factional labels—escalated throughout the 1st century BC, contributing to the Republic's eventual collapse.

Case Studies: Ideology or Opportunism?

Caesar: The Popularis Dictator

Caesar consistently used popularis methods—appealing to assemblies, distributing land to veterans, providing public entertainment. Yet his ultimate goal was personal power, not popular democracy. His career shows how factional labels could mask autocratic ambitions.

Cicero: The Flexible Bonus

Cicero claimed to lead the boni and defend Republican traditions, yet he allied with Pompey's extraordinary commands and even considered joining Caesar. His career demonstrates how even principled politicians adapted their factional alignment to circumstances.

Clodius: Popularis or Gangster?

Clodius used classic popularis methods—tribunician power, popular assemblies, appeals to the urban poor. However, his policies seemed designed more to pursue personal vendettas and political dominance than genuine reform. His career questions whether popularis methods necessarily served popularis goals.

The Collapse of Factional Politics

As the Republic weakened, factional labels became increasingly meaningless. The rise of military commanders with personal loyalty from troops, and the increasing use of violence, bribery, and populism, all contributed to the erosion of Republican norms and paved the way for dictatorship and monarchy.

The final civil wars (49-31 BC) saw former allies and enemies constantly switching sides based on personal advantage rather than factional principle. Mark Antony began as Caesar's popularis lieutenant but ended as an Eastern monarch. Octavian claimed to defend Republican tradition while systematically destroying Republican institutions.

The ultimate irony: Politicians who claimed to defend particular factional ideals often became the greatest threats to the system that made those factions possible. The Republic was destroyed not by its enemies but by those who claimed to be its champions—whether optimates, populares, or boni.

Modern relevance: The Roman experience shows how political labels can become disconnected from political reality. Understanding the gap between factional rhetoric and factional practice is essential for analysing any political system—ancient or modern.