1.4 Political Ideals

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will understand the key political ideals that shaped Republican discourse, how figures like Cicero and Cato embodied these values, and the tension between idealistic rhetoric and political reality in the Late Republic.

The Roman Republic was not only a system of institutions but also a set of deeply held values. These ideals shaped how Roman politicians presented themselves, what they claimed to defend, and how they judged their opponents. While often sincerely believed, they could also be used as rhetorical tools to justify ambition and denounce rivals.

Understanding these ideals is key to interpreting the actions and words of figures like Cicero, Cato, Caesar, and others. The tension between high-minded principles and political pragmatism defined much of Late Republican discourse.

Roman politics was shaped by a complex set of values that guided—or were claimed to guide—political behaviour. Explore each ideal to understand its meaning, importance, and how it was used (or misused) by Republican politicians.

Roman Political Values

Click on any ideal above to explore its meaning, historical significance, and how it was used in Late Republican politics. These concepts were not merely abstract principles—they were powerful tools of political rhetoric that could justify actions, attack enemies, and rally support.

Key insight: The same ideal could be interpreted differently by different politicians. Understanding how these values were manipulated is essential for grasping the complexity of Republican political discourse.

Dignitas: The Currency of Roman Politics

Dignitas meant personal worth, honour, and reputation. It was earned through military victories, public service, oratory, and the visible support of the people. For Roman aristocrats, dignitas was more precious than life itself.

How it was gained:

- Military commands and victories (imperium)

- Successful prosecution or defence in court

- Holding high magistracies, especially the consulship

- Giving magnificent games or public works

- Impressive oratory in the Senate or Forum

Political consequences: A man's dignitas was central to his public image. Losing it—through exile, humiliation, or defeat—was a source of deep shame. Protecting or increasing it often justified ambitious or even illegal acts. Caesar famously claimed he crossed the Rubicon to preserve his dignitas against his enemies' attacks.

The dark side: The pursuit of dignitas could lead to reckless ambition, corruption, and violence. Politicians might start unnecessary wars, prosecute innocent rivals, or break constitutional norms—all in the name of maintaining their honour.

Auctoritas: Influence Beyond Legal Power

Auctoritas referred to influence and prestige—a kind of moral weight that went beyond formal legal authority. It was not the same as imperium, but could often achieve more through persuasion and respect.

Sources of auctoritas:

- Age, experience, and wisdom (especially for senior senators)

- Past achievements and distinguished service

- Reputation for integrity and good judgement

- Skill in oratory and debate

- Family lineage and ancestral honours

How it worked: A senator or statesman with great auctoritas could persuade others, sway debates, and dominate decisions without holding formal office. The Senate as a body claimed collective auctoritas over Roman policy, though it had no legal power to enforce its will.

Cicero's auctoritas: Cicero built his auctoritas on his reputation as Rome's greatest orator, his successful consulship (defeating the Catiline conspiracy), and his defence of Republican traditions. Even as a novus homo without noble ancestry, his auctoritas rivalled that of ancient patrician families.

Its limits: Auctoritas depended on others' willingness to listen and be persuaded. When politicians like Caesar and Pompey commanded armies and vast resources, traditional auctoritas often proved powerless against force.

Libertas: Freedom and Its Contradictions

Libertas (freedom) was a central Republican value, often defined in opposition to tyranny. For Romans, liberty meant freedom from domination by one man—especially a king or dictator—and the ability of citizens to participate in public life.

What libertas meant:

- Freedom from arbitrary rule by kings or tyrants

- The right to vote in assemblies and courts

- Protection under law rather than personal whim

- Opportunity for political participation and advancement

- Economic freedom and property rights

Political weapon: Libertas was used as a justification for opposing figures like Sulla and Caesar. However, its meaning could be twisted. Caesar claimed to defend the libertas of the people against senatorial oppression; the conspirators who killed him claimed to be restoring libertas from his dictatorship.

Contradictions: Roman "freedom" was compatible with slavery, imperial rule over other peoples, and the exclusion of women and non-citizens from political life. Libertas was essentially the freedom of Roman male citizens to compete for power and status—not universal human freedom.

The assassins' claim: Brutus and his fellow conspirators killed Caesar on the Ides of March claiming to restore libertas to Rome. Yet their action triggered civil wars that ultimately destroyed the Republic they claimed to defend.

Concordia Ordinum: Cicero's Impossible Dream

This phrase, coined by Cicero, means "harmony of the orders"—the idea that the senatorial and equestrian classes should cooperate to govern Rome. Cicero saw this alliance as the best hope for preserving Republican order.

Cicero's vision:

- Senators would provide political leadership and wisdom

- Equites would supply financial expertise and business acumen

- Together they would resist popularis demagogues and military strongmen

- Shared interests would create stability and good governance

- Traditional values would be preserved against revolutionary change

Why it appealed: As a novus homo, Cicero had experienced both worlds—rising from equestrian rank to the consulship. He understood both groups' perspectives and genuinely believed they could work together for Rome's benefit.

Why it failed: In reality, tensions between these orders often led to political conflict and violence. The equites wanted profitable tax contracts and business opportunities; senators often saw them as greedy and short-sighted. Economic interests frequently clashed with political principles.

Historical irony: Cicero's own fate illustrated the failure of concordia ordinum. Despite his efforts to unite the elite, he was eventually proscribed and murdered by Mark Antony—with the acquiescence of senators who should have been his natural allies.

Otium cum Dignitate: The Peaceful Republic

Literally "leisure with dignity," this phrase expressed the ideal state of peace where the elite could live a quiet life of reflection, culture, and political stability—with dignity intact. Cicero used it to describe his vision of a peaceful, hierarchical Republic.

What it envisioned:

- Internal peace with no civil wars or street violence

- Stable constitutional government respecting tradition

- Time for intellectual pursuits, literature, and philosophy

- Dignified retirement for elder statesmen

- Prosperity allowing cultural flourishing

Personal longing: Cicero's letters often show a yearning for this state of affairs, especially in later life as political violence escalated. Torn between duty to the Republic and desire for safety, he frequently expressed nostalgia for peaceful times.

Class privilege: This ideal essentially assumed that the upper classes could enjoy cultured leisure while others did the work of governing and defending the state. It reflected aristocratic values rather than democratic ideals.

Historical impossibility: The Late Republic never achieved otium cum dignitate. Instead, it was characterised by constant political struggle, violence, and civil war. Peace would only come under Augustus—but at the price of Republican freedom.

Virtus: The Warrior's Excellence

Virtus originally meant "manliness" (from vir, man) but came to encompass courage, excellence, and moral strength. It was the fundamental quality expected of Roman leaders, especially in military contexts.

Military virtus:

- Courage in battle and willingness to face death

- Leadership ability and tactical skill

- Loyalty to comrades and dedication to victory

- Endurance under hardship and discipline

- Protection of Roman honour and territory

Civic virtus: The concept expanded to include moral excellence in political life—honesty, integrity, putting public good above private gain, and devotion to Republican traditions.

Competing claims: All major Late Republican figures claimed virtus. Caesar demonstrated it through military genius; Pompey through his victories in the East; Cato through moral inflexibility; Cicero through oratorical defence of the state.

Gender implications: Virtus was explicitly masculine—women were excluded from this ideal. This reinforced male dominance in politics and warfare while limiting concepts of civic excellence to half the population.

Paradox: The pursuit of virtus could lead to its opposite. Politicians seeking to demonstrate their excellence might engage in unnecessary wars, corrupt practices, or violent competition—destroying the very values they claimed to embody.

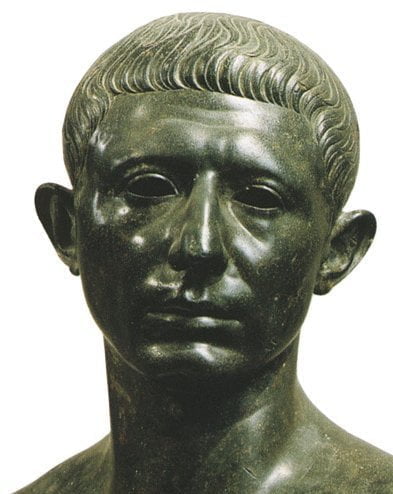

Marcus Porcius Cato

"The Younger" (95-46 BC)

The Stoic Politician

Cato the Younger was the most prominent example of Stoic philosophy applied to Roman politics. Unlike most politicians who adapted their principles to circumstances, Cato refused all compromise with what he saw as corruption or tyranny.

His reputation: Even his enemies admitted Cato's integrity. Caesar called him "the only man who attempted the revolution with a sober mind," whilst Cicero praised his consistency—though sometimes criticising his inflexibility.

Stoic Political Principles

- Duty above personal gain: Public service as moral obligation, not career opportunity

- Reason over emotion: Decisions based on logic and principle, not passion or expedience

- Virtue as the highest good: Integrity more valuable than success, wealth, or popularity

- Resistance to corruption: Refusing compromises with vice, even for "greater good"

- Acceptance of fate: Focusing on what can be controlled, accepting what cannot

- Death before dishonour: Suicide preferable to living under tyranny

Cato's Political Career: Principle in Practice

As Quaestor (64 BC): Refused all bribes and investigated corruption in the treasury, recovering vast sums stolen by previous magistrates. He insisted on written receipts for all transactions, revolutionising financial administration.

Opposition to the Triumvirate: Alone among major politicians, Cato consistently opposed the First Triumvirate. When Caesar offered to make him son-in-law and partner, Cato refused, seeing it as corruption of the Republican system.

Filibustering Caesar's Land Bill: Used constitutional procedures to block legislation he saw as unconstitutional, speaking until nightfall to prevent votes. When Caesar had him physically removed from the Senate, Cato became a martyr for Republican traditions.

The Utica Suicide (46 BC): Rather than accept Caesar's clemency after Thapsus, Cato killed himself. His suicide became the ultimate symbol of Republican resistance—dying free rather than living under a tyrant.

Contemporary reactions: Caesar was reportedly furious at being denied the opportunity to show mercy. Cicero wrote a eulogy praising Cato's virtue. The suicide inspired both admiration and criticism—was it noble principle or stubborn pride?

Stoic legacy: Cato showed both the power and limitations of philosophical principles in politics. His unwillingness to compromise may have hastened the Republic's collapse, but it also preserved the ideal of virtue against overwhelming corruption.

📜 Republican Ideals

- Libertas: Freedom from tyranny for all citizens

- Virtus: Moral excellence and courage in service

- Dignitas: Honour earned through merit

- Auctoritas: Influence based on wisdom and experience

- Concordia: Harmony between different social orders

⚔️ Political Reality

- Power struggles: Violent competition for dominance

- Corruption: Bribery, extortion, and illegal enrichment

- Manipulation: Using ideals as rhetorical weapons

- Violence: Street gangs and civil wars

- Self-interest: Personal ambition over public good

Case Studies: Ideals in Action

Caesar and Dignitas

Caesar claimed that crossing the Rubicon was necessary to preserve his dignitas against enemies who sought to prosecute and humiliate him. This showed how personal honour could be used to justify actions that destroyed the Republic itself.

Cato's Stoic Virtue

Cato the Younger embodied Stoicism in his politics—refusing to compromise principles, even when flexibility might have saved the Republic. His suicide at Utica (46 BC) rather than live under Caesar became a symbol of Republican resistance.

Cicero's Concordia Ordinum

Cicero spent his career trying to unite senators and equites in defence of the Republic. His failure showed the difficulty of creating lasting political alliances based on shared ideals rather than material interests.

Cynicism and Political Realism

Not all figures believed in, or acted by, these ideals. Politicians like Caesar and Clodius could be seen as manipulators of tradition, cloaking ambition in traditional rhetoric. Some scholars argue that ideals such as libertas and dignitas were often invoked hypocritically—to preserve elite control or justify personal ambition.

The historian's perspective: Sallust, writing after the Republic's collapse, argued that traditional values had been corrupted by wealth and ambition. He saw the Late Republic as an era when noble ideals were used to disguise ignoble motives.

Modern scholarly debate: Historians continue to argue about whether Late Republican politicians genuinely believed in traditional values or cynically manipulated them. The truth likely varied by individual and circumstance—some leaders were sincere idealists, others calculating opportunists, and many fell somewhere between.

The Power and Peril of Political Ideals

Roman political ideals were both the strength and weakness of the Republic. They provided a shared vocabulary of values that could inspire great deeds and noble sacrifices. Cato's principled resistance, Cicero's oratorical defence of tradition, and the conspirators' willingness to kill Caesar all drew their power from these ideals.

Yet the same ideals could be manipulated to justify ambition, violence, and the destruction of the very system they claimed to protect. When Caesar crossed the Rubicon "to preserve his dignitas," when Pompey claimed to defend the Republic whilst accumulating unprecedented power, when Brutus murdered a fellow senator "to restore libertas"—all were using traditional values to justify revolutionary actions.

The ultimate irony: The Roman Republic was destroyed by men who claimed to be its greatest defenders, using the very ideals that had once made it great. Understanding this paradox is essential for grasping both the nobility and the tragedy of the Late Republic.